Author Corey Recko

Sign up for the

The First Plot to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln,

and How the Pinkertons Protected the President-elect

by

Corey Recko

Available in the store:

It is well known that Abraham Lincoln's life was ended in 1865 by a bullet to the back of the head fired by John Wilkes Booth. What is not as widely known is that there were plots to assassinate Lincoln as far back as 1861. If these plots had been carried out, Lincoln's life would have ended before his presidency even began. What this would have meant for the country can only be speculated. It is possible that if Lincoln were assassinated at that time, the Confederate States of America would exist today. The following is the account of how the plots against Lincoln were discovered and thwarted by a small group of skilled detectives.

Abraham Lincoln's election as President of the United States happened at a time when the issue of slavery divided the nation. The split between the North and the South grew larger in the 1850s as the debate centered on whether the territories would be admitted to the Union as slave or free states. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 left the issue of slavery up to each individual territory. This left both sides dissatisfied and led to bloodshed as supporters of both positions populated the territories to influence the vote.

Five years later, in October of 1859, fanatical abolitionist John Brown and a group of followers attacked Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in the hope of seizing the weapons in the armory and inciting a slave insurrection. While the attack failed in its intended purpose, what it did accomplish was to deepen the divide between North and South. The southerners feared more violence from northern abolitionists if they remained with the Union.1 This was the attitude of the country at the close of the decade.

The slavery debate became so divisive in the Democratic party that it tore them in two after the nomination of Stephen A. Douglas for President. Douglas believed that each territory should have the right to decide whether to allow slavery within its borders. This was unacceptable to the southern radicals. They believed that slavery should be allowed in all the territories, so they nominated their own candidate, John C. Breckinridge. Douglas and Breckinridge split the Democratic vote, allowing Republican Abraham Lincoln to win the 1860 election with only 39.9% of the vote.2

Even though Lincoln had no intention of attacking slavery in the South and only opposed its extension into the territories, many southerners saw him as an abolitionist who wanted to end slavery once and for all. This led to seven states seceding from the United States before Lincoln even took office. They banded together to form the Confederate States of America. Following Lincoln's inauguration four more states joined the CSA.3

Feelings and fears were obviously running high when Lincoln was elected as the sixteenth President of the United States. Shortly after the election, detective Allan Pinkerton, owner of a private detective agency in Chicago, was contacted by Samuel Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, about threats by secessionists to destroy bridges and railroad tracks connecting Washington, D.C., to New York City. The threats were coming from Maryland, a state with a population that was split on the secession issue.

Allan Pinkerton brought a group of detectives with him to meet with railroad representatives in Philadelphia, and from there they traveled to Baltimore to investigate. Pinkerton and three operatives remained in Baltimore. They were Harry W. Davies, Kate Warne, and a man who used the alias Charles D. C. Williams. Two others, Timothy Webster and Hattie Lewis, posing as husband and wife, went to Perrymansville (now Perryman), Maryland.4 What these detectives uncovered was much more serious than plot to destroy railroad bridges.

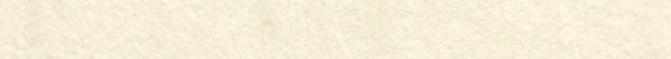

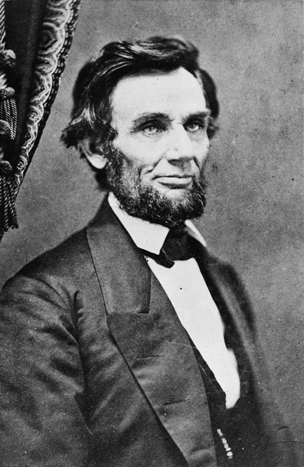

Abraham Lincoln, May 20, 1860

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-23081

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

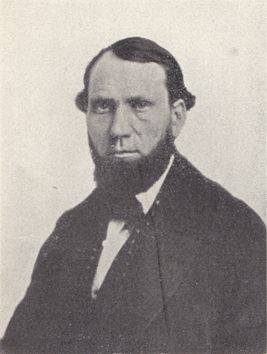

Allan Pinkerton, 1860.

Author's collection.

Pinkerton rented an office in Baltimore and posed as a stockbroker under the alias John H. Hutcheson. The adjoining office space was occupied by James H. Luckett, a stockbroker who was dedicated to the Maryland secessionist cause. Luckett was part of a group debating whether Maryland should secede from the Union.5

Pinkerton quickly became friendly with Luckett and expressed his pretended southern sympathies to him, leading Luckett to confide in Pinkerton. On February 15, 1861, Pinkerton and Luckett discussed a convention that was debating the secession question. Luckett expressed the opinion that Maryland needed to-and soon would-secede from the Union. Of Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks, who opposed secession, Luckett said, “I tell you my friend, it will be but a short time until you will find Governor Hicks will have to fly, or he will be hung-He is a traitor to his God and his Country.”6

Pinkerton then brought up the fact that Lincoln would pass through Baltimore on his way to Washington, to which Luckett replied, “He may pass through quietly but I doubt it. There are a great many men in this city Mr. Hutcheson-good men-aye, and good blood too.”

Pinkerton pointed out that the police had promised Lincoln safe passage, to which Luckett replied, “Oh! That is easily promised, but may not be so easily done.” Luckett continued to rail against “Lincoln and his Abolitionist Crew.” Pinkerton, to show his pretended loyalty to the South, gave Luckett $25, telling Luckett that he would like it used for Southern rights. He then advised Luckett to be “cautious in talking with outsiders . . . .”

Pinkerton, in his daily reports, recorded Luckett's response: “Mr. Luckett said they were exceedingly cautious as to who they talked with; that they knew who they talked with; that some time ago they found that the Government had spies amongst them, and that since then they had been very careful; that none knew anything about the movements of the Southern rights men, but such as were sworn to keep it secret; that he (Mr. Luckett) was not a member of the secret organization, for there were but very few, who could be admitted, but he knew many who were . . . .”7 The secret organization Luckett referred to was probably the local branch of the Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society whose goal at one time was to form a slaveholding nation that included the southern United States, the West Indies, Mexico, and parts of Central America. The society shifted its efforts to Southern independence following Lincoln's election.8 Luckett then told Pinkerton about a leading member of the organization, Cipriano Ferrandini, a thirty-eight year old hairdresser who had been born on the French island of Corsica. Corsica was populated by many people of Italian decent and Italian was one of its official languages. Because of this, Luckett believed that Ferrandini was Italian. When speaking of Ferrandini, Luckett referred to him as “captain,” a title that was likely a reference to Ferrandini's rank in the Knights of the Golden Circle or his rank in a local militia called the Constitutional Guards.9 Of his role in this pro-secession group, Luckett told Pinkerton that Cipriano Ferrandini was the leading man and ready to lose his life for the South. Luckett said that Ferrandini “had a plan fixed to prevent Lincoln from passing through Baltimore, and would certainly see that Lincoln never should go to Washington . . . .”

Luckett asked if Pinkerton would meet him at Barr's Saloon on South Street that evening so Luckett could introduce him to Ferrandini. Of course Pinkerton accepted the invitation and they agreed to meet there at 7:00 p.m.

Pinkerton reported,

After supper I went to Barr's Saloon, and found Mr. Luckett and several other gentleman there. He asked me to drink and introduced me to Captain Ferrandina [sic], and Captain Turner. He eulogized me very highly as a neighbor of his, and told Ferrandina that I was the gentleman who had given the Twenty five Dollars, he (Luckett) had given to Ferrandina. |

The conversation at once got into Politics, and Ferrandina who is a fine looking, intelligent appearing person, became very excited. . . . He has lived South for many years and is thoroughly imbued with the idea that the South must rule; that they (Southerners) have been outraged in their rights by the election of Lincoln, and [are] freely justified resorting to any means to prevent Lincoln from taking his seat, and as he spoke his eyes fairly glared and glistened, and his whole frame quivered, but he was fully conscious of all he was doing. He is a man well calculated for controlling and directing the ardent minded-he is an enthusiast, and believes that, to use his own words, “Murder of any kind is justifiable and right to save the rights of the Southern people.” In all his views he was ably seconded by Captain Turner.10 |

William H. H. Turner was a Baltimore Circuit Court clerk.11 The report continued:

Captain Turner is an American, but although, very much of a gentleman and possessing warm Southern feelings, he is not by any means so dangerous a man as Ferrandina . . . he is entirely under the control of Ferrandina. In fact it could not be otherwise, for even I myself felt the influence of this man[']s strange power, and wrong though I knew him to be, I felt strangely unable to keep my mind balanced against him. |

Ferrandina said that never, never shall Lincoln be President-His life (Ferrandina) was of no consequence-he was willing to give it for Lincoln's . . . [he was] ready to die for his country, and the rights of the South, and, said Ferrandina, turning to Captain Turner[,] “we shall all die together, we shall show the North that we fear them not-every Captain, said he, will on that day prove himself a hero. The first shot fired, the main Traitor (Lincoln) dead, and all Maryland will be with us, and the South shall be free, and the North must then be ours.” “Mr. Huchins [sic],” said Ferrandina, “If I alone must do it, I shall-Lincoln shall die in this City.” |

The men were sitting alone in the corner of the barroom and, while talking, noticed that two strangers had moved near them. Luckett, who thought the men were listening to them, mentioned their presence to Ferrandini. They went to the bar, where Pinkerton bought the group a round of drinks, then, at Ferrandini direction, they went to another part of the room to see if the strangers would follow, which they did. Ferrandini suspected they were spies. He had a secret meeting to attend that night and was worried the strangers would follow, so Luckett and Pinkerton stayed to make sure the men didn't follow-they didn't-while Ferrandini and Turner left for the meeting. Soon Pinkerton and Luckett parted ways. Pinkerton went to his hotel room for the night, arriving there about 9:00 p.m.12

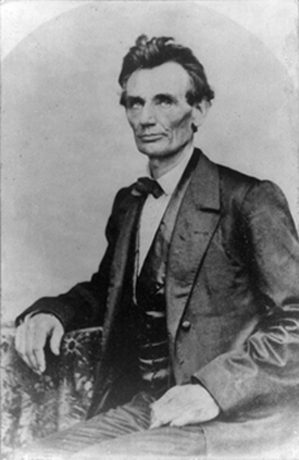

Abraham Lincoln, February 9, 1861.

Photograph by C. S. German

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-7334

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

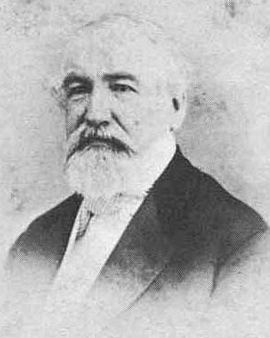

Norman B. Judd

Date and photographer unknown.

Wikimedia Commons.

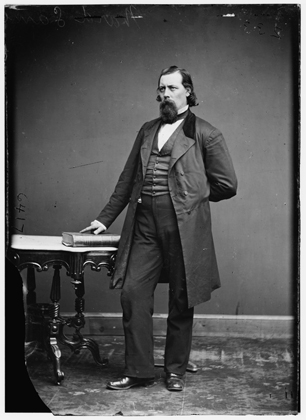

Ward Lamon, circa 1855-1865.

Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-cwpbh-02904

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Pinkerton and Judd worked that night to develop the plan to take Lincoln to Washington. Also at the meeting were Henry Sanford of the American Telegraph Company and George C. Franciscus of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Sanford was needed for communication and to ensure that the telegraph line was cut so word of Lincoln's early departure could not be sent ahead and Franciscus was there to set up transportation.26

The next morning, information about the plots to assassinate Lincoln came from General Winfield Scott, which confirmed to Lincoln that the threats were real.27

The evening of February 22nd, Abraham Lincoln attended a banquet held by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew G. Curtin. Feigning sickness, Lincoln left early. Wearing a brown Kossuth hat and “an overcoat thrown loosely over his shoulders” for disguise, Lincoln left with Ward Lamon for the train station. At the station, the men were greeted by Allan Pinkerton. Kate Warne was already in the sleeping car. Lincoln, Lamon, and Pinkerton went in and the train soon left. It would pass through Baltimore and arrive in Washington in the morning.28 Kate Warne, who would leave the group in Baltimore, reported,

Just before the train started Mr P- accompanied by Mr. Lincoln and Col. Lamon came into the Car. I showed Mr. P- the berths and everything went off well. Mr. P- introduced me to Mr. Lincoln. He talked very friendly for some time-we all went to bed early. Mr. P- did not sleep, nor did Mr. Lincoln. The excitement seemed to keep us all awake. Nothing of importance happened through the night. |

Mr. Lincoln is very homely, and so very tall that he could not lay straight in his berth.29 |

Pinkerton commented on the light mood among the travelers in his report, while recounting the train's stop in Baltimore, which was from 3:30 until their car was transported to another depot and that train left at 4:15 a.m.

while at the latter [Baltimore] Depot we had considerable amusement by the repeated calls of the Night Watchman of the Company to rouse the Ticket Agent who appeared to be asleep in a wooden building close by the sleeping car. He repeatedly attempted to awaken the sleepy Official, by pounding on the side of the building with a club, and hallowing “Captain its [sic] Four o'clock.” This he kept up for about twenty minutes without any change in the time, and many funny remarks were made by the passengers at the Watchman[']s time being always the same. Mr. Lincoln appeared to enjoy it very much and made several witty remarks showing that he was as full of fun as ever.30 |

They arrived safely in Washington, D.C., at 6:00 a.m.

When news of Lincoln's secret journey went public he was mocked in the press for the caution taken. These reporters did not have all the facts. Considering the threats that existed, the precautions taken seem not only reasonable but absolutely necessary. Had he been allowed to follow his public itinerary, a crowd would have met him in Baltimore, and among this crowd would have been Southern sympathizers, some of whom wanted Lincoln dead as they believed he was responsible for all of the troubles facing the nation. Among them were a select few who had planned his assassination.

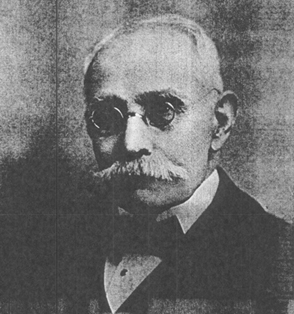

Cipriano Ferrandini in later years.

Archives of Maryland.

Over the years, some have questioned whether there actually was a plot to kill Lincoln, or whether Pinkerton exaggerated it for his own gain. This idea began with Ward Lamon, who had a personal grudge against Pinkerton. The fact that outside sources also learned of these threats is just one of the confirmations of Pinkerton's reports. While there may not have been a single, well organized plot to assassinate the President-elect, the evidence clearly shows that there were a number of threats from groups and individuals. Had Allan Pinkerton and his operatives not uncovered these threats and protected Lincoln, it might have been Cipriano Ferrandini in 1861 and not John Wilkes Booth in 1865 that ended Lincoln's life. Those four extra years would prove to be very important for the nation. For that we owe gratitude to the detectives: Allan Pinkerton, Timothy Webster, Hattie Lewis, Charles D. C. Williams (an alias?), William H. Scott, Kate Warne, and Harry W. Davies.

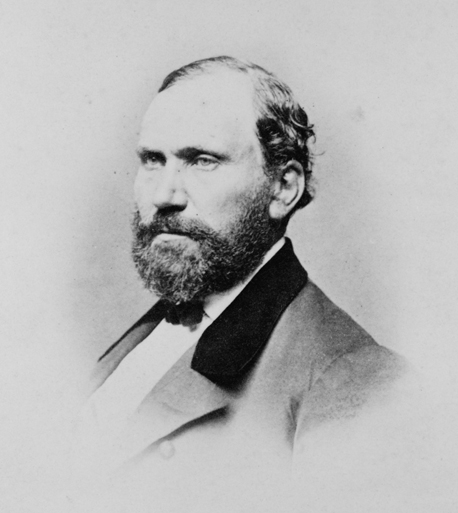

Allan Pinkerton, 1861.

Photograph taken at the Mathew Brady Studio.

Records of Pinkerton's National Detective Agency, box 4, folder 6.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

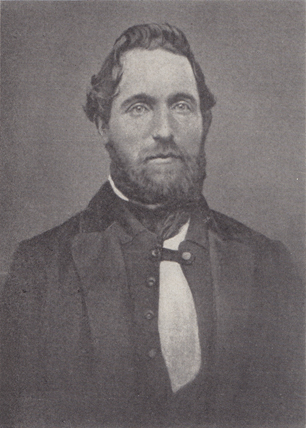

Timothy Webster, 1860.

Reprint from Timothy Webster: Spy of the Rebellion, by Robert A. Pinkerton and William A. Pinkerton.

Author's collection.

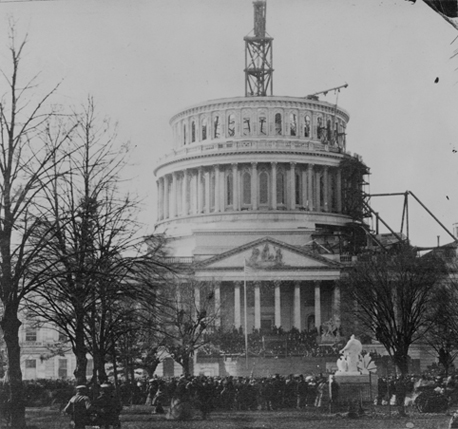

Inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln at the Capitol, March 4, 1861.

Reproduction number: LC-USZ62-48564.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

1 Ketchum, Richard M. (ed.), and Bruce Catton, The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War, 11-12; Konstam, Angus (ed.), The American Civil War: A Visual Encyclopedia, 266; Oates, Stephen B., To Purge this Land With Blood: A Biography of John Brown, 212, 265, 292-93, and 320.

2 Ketchum, Richard M. (ed.), and Bruce Catton, The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War, 48; Konstam, Angus (ed.), The American Civil War: A Visual Encyclopedia, 158; The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Volume 2, 67.

3 Ketchum, Richard M. (ed.), and Bruce Catton, The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War, 50; Konstam, Angus (ed.), The American Civil War: A Visual Encyclopedia, 136 and 439; Oates, Stephen B., With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, 199-201.

4 Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 3, 24, 26, 28, 32, 40, 45, and 50; Horan, James D., The Pinkertons: The Detective Dynasty That Made History, 52-53; Horan, James D., and Howard Swiggett, The Pinkerton Story, 81; Mackay, James, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye, 97; Recko, Corey, A Spy for the Union: The Life and Execution of Timothy Webster, 51.

5 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 15, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library; Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 2, 5, and 76; Mitchell, Charles W., Maryland Voices of the Civil War, 483.

6 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 15, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library; Radcliffe, George L. P., Governor Thomas H. Hicks of Maryland and the Civil War, 34-35.

7 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 15, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

8 Long, Christopher, “Knights of the Golden Circle,” http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/KK/vbk1.html.

9 1850 Federal Census for Baltimore, Baltimore County, Maryland: Cipriano Ferrandini; Death Certificate for Cipriano Ferrandini, December 20, 1910, Maryland State Archives, http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/014400/014473/html/14473sources.html; Tidwell, William A., Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln, 229; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Alleged Hostile Organization Against the Government Within the District of Columbia, 36th Congress, 2d session, Report 79, 133.

10 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 15, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

11 Tidwell, William A., Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln, 229.

12 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 15, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

13 Ibid., 28; Tidwell, William A., Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln, 227.

14 Davies, Harry report, February 12, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

15 Davies, Harry report, February 19, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

16 U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Alleged Hostile Organization Against the Government Within the District of Columbia, 36th Congress, 2d session, Report 79, 1 and 144.

17 Davies, Harry report, February 19, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

18 Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 4.

19 Webster, Timothy report, February 17, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

20 Lamon, Ward H., The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration as President, 505 and 508-10; Mackay, James, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye, 99.

21 Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 41 and 44; Mackay, James, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye, 74.

22 Mackay, James, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye, 99-100.

23 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 21, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library; Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 5.

24 Oates, Stephen B., With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, 208; Pinkerton, Allan report, February 21, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

25 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 21, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

26 Ibid., 69 and 74; Recko, Corey, A Spy for the Union: The Life and Execution of Timothy Webster, 56-57.

27 Horan, James D., and Howard Swiggett, The Pinkerton Story, 85-86; Mackay, James, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye, 101; Pinkerton, Allan, History and Evidence of the Passage of Abraham Lincoln from Harrisburg, Pa., to Washington, D.C., on the Twenty-Second and Twenty-Third of February, Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-One, 20-21.

28 Oates, Stephen B., With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, 211-12; Cuthbert, Norma B. (ed.), Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861: From Pinkerton Records and Related Papers, 77; James D., and Howard Swiggett, The Pinkerton Story, 86; Rowan, Richard Wilmer, The Pinkertons: A Detective Dynasty, 105.

29 Warne, Kate report, February 22, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

30 Pinkerton, Allan report, February 23, 1861, Herndon-Weik Collection of Lincolniana, LN 2408, volume 3, the Huntington Library.

Another operative, Harry Davies, learned about Ferrandini through secessionist Otis K. Hillard.13

Davies reported that on Tuesday, February 12th, he spent much of the day and night with Hillard and was introduced by Hillard to others who wished to help the Southern cause. That evening Hillard introduced Davies to a man named Starr, a reporter for a Baltimore paper, who was said to be about thirty years old. After having a drink together they parted with Starr and then the pair ate at Mann's Restaurant and followed that with a trip to Harry Hemling's Billiard Room. They continued their busy night by at the Pagoda Concert Saloon where they stayed until about 10:00 p.m., at which time Hillard suggested a trip to Annette Travis's brothel. Davies waited patiently as Hillard “and his woman . . . hugged and kissed each other for about an hour . . . .” When they finally left they went to where Davies was staying and talked until about 1:00 in the morning, during which time Hillard told Davies that Company No. 4 of the National Volunteers had drilled that night, and that the company Hillard belong to would drill the next night. Hillard asked Davies if he “had seen a statement of Lincoln's route to Washington City . . . .”

After Davies responded affirmatively, Hillard said, “By the By, that reminds me that I must go and see a certain party in the morning the first thing.” Davies asked Hillard what he must see the person about and Hillard replied, “About Lincoln's route, I want to see about the telegraph in Philadelphia and New York and have some arrangements made about telegraphing.”

“How do you mean?” Davies asked.

“Suppose that some of Lincoln's friends would arrange so that the telegraph messages should be mis-carried, we would have some signs to telegraph by; for instance supposing, that we should telegraph to a certain point 'all up at 7,' that would mean that Lincoln would be at such a point at 7 o'clock.”

Davies questioned Hillard about what their plans were, to which Hillard responded “My friend, that is what I would like to tell you, but I dare not-I wish I could-anything almost I would be willing to do for you, but to tell you that I dare not.” Hillard twice warned Davies “anything that I have said to you be careful not to mention.” Davies recorded in his reports to Pinkerton that Hillard left him “at 1 o'clock in the morning and went to stay all night, or the balance of it with his woman at Annette Travis' house of prostitution No. 70 Davis Street, as he had promised her to come, so he said,” and added that during the past day Hillard “did not drink as much liquor as usual. He appeared melancholy most of the time that he was with me.” He also noted that at some point during the evening they attempted to visit Cipriano Ferrandini at his barbershop but Ferrandini was not in.14

On February 19th, Hillard, at his room, greeted Davies by asking, “You look sober-what is the matter with you?” The men then began a conversation about Abraham Lincoln and the state of the country. Davies went on to question Hillard about the National Volunteers as they went to eat in a private dining room at Mann's Restaurant. Hillard told Davies that ever since he was called to Washington he was “very careful” with what he said. He warned, “There are government spies here all the time, even now, do you see that old man at the other end of the Room? This is the first time I have noticed him-just as likely as not he is a government spy-there is no telling-and may be before this he has my name down, and what I have said. We [the National Volunteers] are all more careful-twenty times more careful than we were previously. I never recognize any of the boys now in the Street when I see them-We have to be careful. Do not think my friend that it is a want of confidence in you that makes me so cautious, it is because I have to be. I do not remember to have spoken to a person out of our Company, and the first thing I knew I was at Washington before that Committee . . . .”15 The committee Hillard referred to was a congressional committee that held hearings on organizations that were allegedly hostile to the government and located in or near Washington. Hillard was questioned by the committee on February 6th.16 Davies reported that he asked Hillard what the first object of the organization was, to which Hillard replied, “It was first organized to prevent the passage of Lincoln with the troops through Baltimore, but our plans are changed every day, as matters change, and what its object will be from day to day, I do not know, nor can I tell. All we have to do is to obey the orders of our Captain, whatever he commands we are required to do. Rest assured I have all confidence in you, and what I can and dare tell you I am willing to and like to do it-I cannot come out and tell you all-I cannot compromise my honor.”17

Meanwhile, in the town of Perrymansville (now Perrymans), while Pinkerton and Davies learned about dangerous groups though others, operative Timothy Webster joined a secessionist militia cavalry which was likely a company of the National Volunteers. Allan Pinkerton later wrote that Webster's reports (most of which no longer exist) showed “the manner in which the first Military organization of Maryland Secessionists was formed . . . .”18 It appears from Webster's two surviving reports that the information he learned was similar to that obtained by Pinkerton and Davies. One of the reports contained talk of danger to Lincoln. Timothy Webster reported,

Captain Keen and some four or five others then came in, and got up a game of Ten-pins, we played until 1.45. p.m., when Springer, Taylor, and I went in to Dinner-They commenced talking about what route Lincoln would take to Washington. Springer said that he was going over the Philadelphia, Willmington [sic], and Baltimore Rail Road, and Taylor said “No”, that Lincoln would go over the Central Road: that he (Lincoln) had better not come over this road with any Military-for if he did that Boat would never make another [trip?] across the River. Springer replied that they had not better attempt to take any Military over this Road, for if they did Lincoln would never get to Washington. . . . Springer talked some about Lincoln, and said that when Lincoln arrived in Baltimore, they would try to get him out to speak, and if he did come out, he (Springer) would not be surprised if they killed him; that there was in Baltimore about One Thousand men well organized, and ready for anything. I asked if the leaders were good men. Springer said they had the very best men in Baltimore, and that nearly all the Custom House Officers were in the Organization. I could not learn from him any of their names.19

The sum of the intelligence gathered prompted Pinkerton to act. He knew that if just one of the men or groups followed through with their threats the president-elect's life would be in real danger, so he sent a telegram to Norman Judd. Judd was a friend of Lincoln and part of the presidential entourage that was traveling with Lincoln from his home in Springfield, Illinois, to his inauguration in Washington.20

Pinkerton then sent twenty-seven or twenty-eight year old operative Kate Warne to meet the presidential party in New York to deliver a note to Judd warning of the danger in Baltimore. After talking the matter over with Warne, Judd asked her to request that Pinkerton meet him when they were in Philadelphia.21

In Philadelphia, Allan Pinkerton first met with Samuel Felton and then with Norman Judd to express his concerns and his plans to keep Lincoln safe. Then he met with Abraham Lincoln.22 Pinkerton reported,

I alluded to the expressions of Hillard and Ferrandina [sic]; that they were ready to give their lives for the welfare of their Country, as also that their country was South of Mason's and Dixon's line; that they were ready and willing to die to rid their Country of a tyrant as they considered Lincoln to be.

I said that I did not desire to be understood as saying that there were any large number of men engaged in this attempt-but that on the contrary I thought there were very few-probably not exceeding from fifteen to twenty who would be really brave enough to make the attempt,-but that I thought Hillard was a fair sample of this class-a young man of good family, character and reputation-honorable, gallant and chivalrous, but thoroughly devoted to Southern rights, and who looked upon the North as being aggressors upon the rights of that section and upon every Northern man as an Abolitionist, and he (Mr. Lincoln) as the embodiment of all those evils, in whose death the South would be largely the gainers.23

Pinkerton stated the obvious fact that there would be a very large crowd gathered in Baltimore. He added that there would either be no police escort, or an escort by “Disloyal Police.” Pinkerton reported that he told them

the slightest sign of discontent would be sufficient to raise all the angry feeling of the Masses, and that then would be a favorable moment for the conspirators to operate; that again, as by the published route, he (Mr. Lincoln) in taking the Northern Central Rail Road from Harrisburg to Baltimore, would arrive at the Calvert Street Depot, and would have about one mile and a quarter to pass through the city in an open carriage, which would move but slowly through the dense crowd, and that then it would be an easy matter for any assasin [sic] to mix in with the crowd and in the confusion of the moment shoot Mr. Lincoln if he felt so disposed; that I felt satisfied in my own mind that if Mr. Lincoln adhered to the published programe of his route to Washington that an assault of some kind would be made upon his person with a view to taking his life.

During the time I was speaking Mr. Lincoln listened with great attention only asking a question occasionally.

They were interrupted once when Ward Lamon-Lincoln's friend and self-appointed body guard-entered the room to give Lincoln a note.24 Following this, the meeting continued.

After I had concluded Mr. Lincoln remained quiet for a few minutes apparently thinking, when Mr. Judd inquired, “If upon any kind of statement which might be made to him (Lincoln) would he (Lincoln) consent to leave for Washington on the train to-night.” Mr. Lincoln said promptly “No, I cannot consent to this. I shall hoist the Flag on Independence Hall to-morrow morning (Washington's birthday), and go to Harrisburg to-morrow, then I (Lincoln) have fulfilled all my engagements, and if you (addressing Mr. Judd), and you Allan (meaning me) think there is positive danger in my attempting to go through Baltimore openly according to the published programe-if you can arrange any way to carry out your views, I shall endeavor to get away quietly from the people at Harrisburg to-morrow evening and shall place myself in your [hands]. . . .”

Pinkerton proposed that if Lincoln could get away from the Harrisburg engagement “unobserved,” that they should take Lincoln in a sleeping car on the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, which wouldn't require Lincoln to change trains in Baltimore.

Pinkerton reported,

This was finally after some discussion agreed upon, and I promised to see the Superintendant [sic] of the Pennsylvania Rail Road in regard to procuring the special train, and making all the arrangements for the trip. I requested Mr. Lincoln that none but Mr. Judd and myself should know anything about this arrangement. He said that ere he could leave it would be necessary for him to tell Mrs. Lincoln and that he thought it likely that she would insist upon W. H. Lamon going with him (Lincoln), but aside from this no one should know. I said that secrecy was so necessary for our success that I deemed it best that as few as possible should know anything of our movements; that I knew all the men with whom it was necessary for me to instruct my movements, and that my share of this secret should be safe, and that if it only was kept quiet I should answer for his safety with my life.

At 11.00. p.m. Mr. Lincoln left.25