The Myth of Ex-Slave Turned

Civil War Spy John Scobell

by Corey Recko

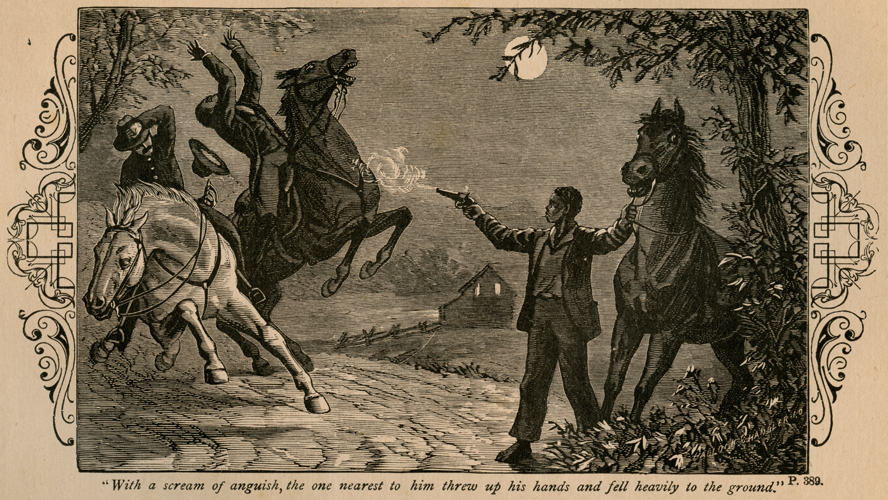

John Scobell shooting a Confederate

pursuer in an illustration for Allan Pinkerton’s book The Spy of the Rebellion.

(Author’s collection)

It

was almost twenty years ago when I first learned of John Scobell. He is said to

be a former slave who became a skilled spy while working under Allan Pinkerton

in the American Civil War. History.com says of him, “Scobell completed a number

of top-secret missions, often playing the part of a cook, field hand or butler

to eavesdrop on Confederate officials. . . .”

According to CIA.gov, “Scobell often worked with two of Pinkerton’s best

agents—Timothy Webster and Carrie Lawton [Hattie Lewis]—posing as a

servant.” I first heard of Scobell while reading Allan Pinkerton’s 1883 Civil War memoir The Spy of the Rebellion.

While it was obvious, with its added dialogue, that the book wasn’t 100%

factual, it was an entertaining read, and it left me with two men, besides

Allan Pinkerton, that I wanted to learn more about. One was the talented spy

Timothy Webster, whose life was cut short following the betrayal of fellow

spies. I spent years researching Webster and wrote a biography (A Spy for the Union: The Life and Death of

Timothy Webster) about this American hero. When I first read about Scobell,

my hope was that I could write a book about him as well. Unfortunately, my

research into Scobell didn’t produce the same results as my Timothy Webster

research.

I

began with secondary sources to find out what was already known about John

Scobell. It wasn’t much. He is written about in plenty of books, but nothing

adds to what Pinkerton wrote in 1883. Curiously, no mention was made of Scobell

in David Horan’s The Pinkertons: The

Detective Dynasty that Made History, a comprehensive history of the agency,

nor does Scobell appear in Edwin Fishel’s very informative and detailed The Secret War for the Union: The Untold

Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War. Were confirmable details

of Scobell’s life so scarce as to make them not worth mentioning? Was his story

not as great as Pinkerton made it out to be? Or was he excluded from these

books because there was no John Scobell? My answer would lie in the Papers of

Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency and the Papers of George Brinton

McClellan.

The

records of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency are very much incomplete for

the 1850s and 1860s. Most were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. But

some records did survive, including a few of Timothy Webster’s handwritten

reports and Pinkerton’s account books from the Civil War years. The problem

with searching the account books for John Scobell, if that was his real name,

was that the account book entries are initials, and Pinkerton also employed

John Scully at the time, so what I was looking for was payments and records

that matched Scobell’s supposed activities as detailed in The Spy of the Rebellion. In this I came up empty. I found no

record of him in any other records or correspondence, either. I was running out

of sources, but I had one major source to go: The papers of General George B.

McClellan, who Pinkerton reported to. These turned out to be a gold mine of

information.

Included

in McClellan’s papers are detailed reports from Allan Pinkerton. While they

don’t include the operatives’ names (again using initials), they contain even minor details of their missions. While this was surely excessive and unneeded

information for the busy General, for the author and historian reading them a

century and a half later, these reports were wonderful. They were invaluable

when writing my biography of Timothy Webster. My search for Scobell was less

satisfying. He wasn’t there. I don’t just mean there wasn’t an operative named John Scobell, but there wasn’t an operative that did anything he was claimed to have done in The Spy of the Rebellion. There wasn’t a record of anyone going on the missions he was said to have undertaken, nor was there a record of anyone ever posing undercover as a

servant for Timothy Webster or Hattie Lewis, as he was said to have

done—not here or in any other account of Webster’s activities. Of those

who recorded their contact with Timothy Webster, no mention was made of anyone

who could have been John Scobell. It was true: John Scobell never existed.

Whether he was added to The Spy of the

Rebellion simply to sell books, or he was character Pinkerton created to

pay tribute to the many runaway slaves who provided him with valuable

information matters little. There was no John Scobell.

But,

if John Scobell didn’t exist, why is he so often written about? A Google search

for “john scobell civil war spy” produces 15,400 results, including first page results from some major news organizations and the CIA. That same search

produces 5,870 results in Google Books. Since it’s no secret that Allan

Pinkerton’s books are partly fictionalized and should never be taken as fact

without corroboration, how did this happen? The problem isn’t that these books,

articles, and websites used The Spy of

the Rebellion as their only source (though, unfortunately, some of them

did). The problem is many used a book that used that book as a source. Or used

a book that used a book that used... you get the picture.

I

have great admiration for Allan Pinkerton. He founded the most successful

private detective agency ever at a time when it was needed for real law

enforcement. He was an innovator in his field, an ardent abolitionist, fighter

for Black rights, and he served his adopted country at a most desperate time.

It is unfortunate that at the end of his life he so clouded the historical

record, and it’s a shame how far the story of a man who never existed has

spread.

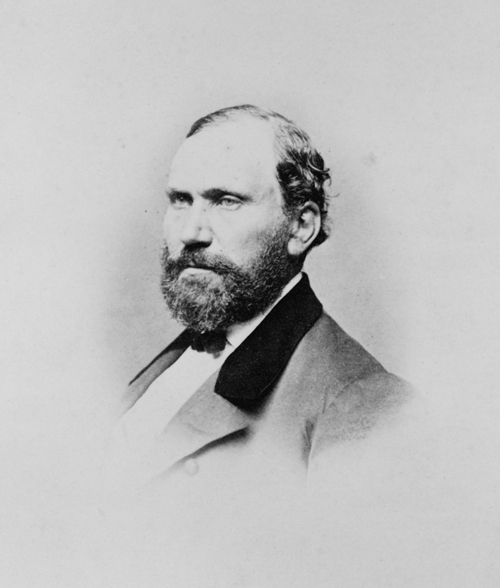

Allan Pinkerton, 1861

Photograph taken at the Mathew Brady

Studio

(Records of Pinkerton’s National

Detective Agency, Library of Congress)

Cover of Allan Pinkerton’s 1883 book The Spy of the Rebellion

(Author’s collection)

© Corey Recko 2019